Background and justification of selected algorithm#

Introduction#

Soil moisture is a crucial part of the Earth’s water cycle and it has been monitored for agricultural purposes, water supply management, climate forecasting, forest fire prediction and land-atmosphere interactions [Dorigo et al., 2017]. Soil moisture is defined as the amount of water held in the soil, and relates to precipitation, evaporation, and plant uptake [Seneviratne et al., 2010]. Changes in soil moisture can have substantial impacts on agricultural productivity, forest and the general ecosystem health.

Soil moisture was identified as an essential climate variable (ECV) by the Global Climate Observing System (GCOS), due to its importance for understanding and monitoring changes in the Earth’s climate system. Soil moisture estimation over large areas and long periods is challenging due to its spatial and temporal variability. However, remote sensing technologies have revolutionized the ability to measure soil moisture over large areas, which has facilitated numerous applications in several fields, including hydrology, agriculture, and climate modeling [Entekhabi et al., 2010].

Accurate and timely measurements of soil moisture are crucial for improving our understanding of the Earth’s climate system and its associated processes [Vereecken et al., 2008]. For instance, monitoring soil moisture can help predict droughts, floods, and landslides, which can save lives and reduce economic losses. It can also help optimize water management and irrigation practices, leading to increased agricultural productivity and efficiency. Furthermore, soil moisture data can improve weather and climate forecasting by improving the accuracy of precipitation estimates and address priority questions on climate change by identifying patterns and trends that affect the Earth’s climate [Koster et al., 2004].

Passive remote sensing of soil moisture is a technique used to estimate soil moisture content over large areas and at high temporal resolution [Kerr et al., 2001]. Passive microwave sensors are used to measure the natural thermal radiation emitted from the soil surface. The intensity of this radiation varies depending on the dielectric properties and temperature of the target medium, which in the case of the near surface soil layer, is influenced by the amount of moisture present in the near surface soil layer. The low microwave frequencies at L-band (~1 GHz) have additional benefits for soil moisture measurement: the atmosphere is almost entirely transparent, making it possible to sense soil moisture regardless of weather conditions and signals from the underlying soil can be transmitted up tp moderate vegetation layers.

Historical heritage#

The history of passive remote sensing for soil moisture estimation dates back to the 1960s. During this period , researchers began to look at ways of using microwaves to measure water content in the soil. The first successful experiments used a single-channel microwave radiometer to measure the brightness temperature of the surface of the Earth. This data was then used to calculate the soil moisture content [Schmugge, 1983]. In the 1970s and 1980s, the number of channels of the radiometer was increased and more sophisticated models were developed to better measure soil moisture. This included the use of multiple frequency bands and polarimetric techniques to better characterize the soil moisture.

In 1978, both Nimbus-7 and the short-lived Seasat were launched, each equipped with the Scanning Multichannel Microwave Radiometer (SMMR) instrument. SMMR, a 10-channel instrument operating at frequencies between 6.6 and 37 GHz, achieved spatial resolutions ranging from approximately 150 km to 30 km. It acted as a precursor to the Advanced Microwave Scanning Radiometer (AMSR) and its subsequent version, AMSR2 [Njoku and Li, 1999]. AMSR was launched in 2002 and it has been used for soil moisture estimation as well as other applications such as sea ice concentration and snow depth. It is the predecessor of the Advanced Microwave Scanning Radiometer 2 (AMSR2), launched in 2012 onboard the GCOM-W1 satellite [Wu et al., 2020].

Passive remote sensing for soil moisture estimation has gone through several iterations, with advances in hardware and software technology allowing for more accurate and precise measurements. Today, passive remote sensing is one of the most widely used methods for soil moisture estimation, with satellites, aircraft, and ground-based instruments all contributing to its knowledge.

Observations from the CIMR (Copernicus Imaging Microwave Radiometer) mission will potentially offer continuity to the brightness temperature and soil moisture measurements obtained from ESA’s SMOS (Soil Moisture Ocean Salinity) [Kerr et al., 2001] and NASA’s SMAP (Soil Moisture Active Passive) [Entekhabi et al., 2010] and Aquarius missions. This continuity also extends to the data from AMSR and AMSR2 instruments.

Physical approach#

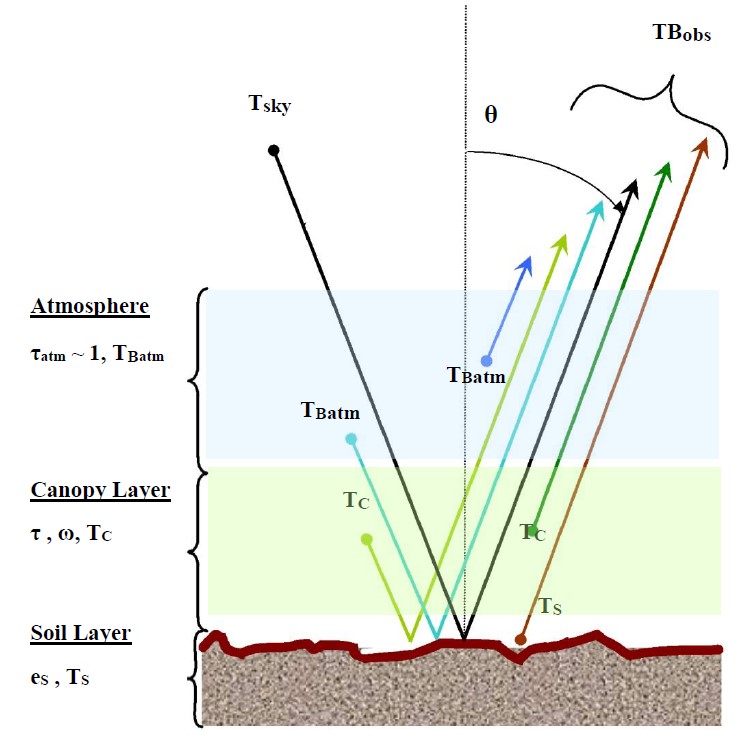

At microwave frequencies, the intensity of emission is proportional to the surface temperature and emissivity, which is commonly referred to as brightness temperature (TB) using the Rayleigh-Jeans approximation. When the microwave sensor orbits above the Earth, the observed TB includes energy from the soil (attenuated by the vegetation), and vegetation, downwelling atmospheric emission and cosmic background emission reflected by the surface and attenuated by vegetation, and the upwelling atmospheric emission (Fig. 1). The atmosphere transmissivity (τatm) is approximately equal to 1, and the cosmic background temperature (Tsky) is around 2.7 K.

Fig. 1 Contributions to the Top Of Atmosphere (TOA) brigthness temperature [from SMOS ATBD, ref. 12 and SMAP ATBD, Figure 2]#

The passive microwave radiometry community typically use the zeroth-order solution to the radiative transfer equation (known as the tau-omega model [Mo et al., 1982]) to simultaneously characterize surface and vegetation emission. It takes into account the impact of a layer of vegetation covering the soil, which affects the emission of the soil and adds to the overall radiative flux its own emission. The process of obtaining soil moisture and microwave vegetation parameters from CIMR TB observations involves inverting this model, which will be conducted for L-band TBs at their native resolution (<60 km) and for L-band TBs sharpened with C/X-band TBs to achieve an enhanced resolution (~15 km).

Justification of selected algorithm#

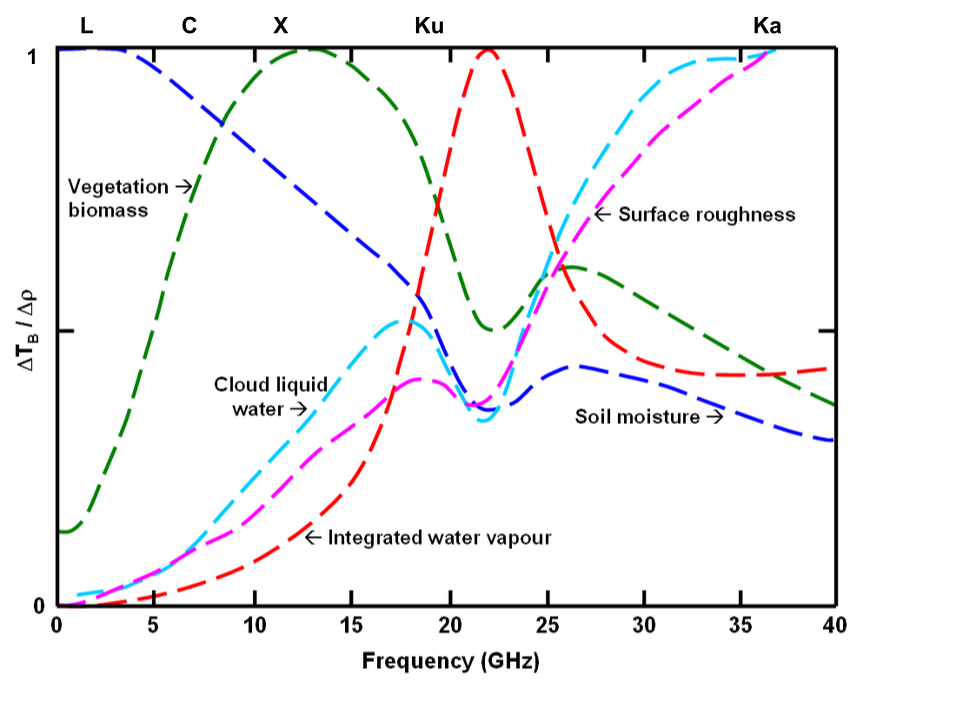

In this section, we justify the selection of our proposed algorithm, which is founded on the SMOS-IC algorithm for SMOS [Fernandez-Moran et al., 2017, Wigneron et al., 2021] and dual channel algorithms developed for SMAP [Konings et al., 2016, Konings et al., 2017, Chaubell et al., 2022, Li et al., 2022]. The proposed algorithm makes use of both H-polarized and V-polarized TB observations to estimate soil moisture and vegetation optical depth, \(𝜏\) at L-band. The choice of this band is attributed to its ability to penetrate deeper into vegetation, providing more accurate measurements. At increasing vegetation cover, the transmissivity decays to a lower extent for L-band (1.4 GHz) as compared to higher frequencies, such as C-band (6.9 GHz) and X-band (10.6 GHz), which are also sensitive to soil moisture but to a lesser extent [Kerr, 1996, Kim et al., 2018, Link et al., 2019]. Various factors, including vegetation biomass, cloud liquid water, soil moisture, surface roughness, and integrated water vapour, influence the TB differently across each CIMR band, as illustrated in the referenced figure (Fig. 2). Considering that the highest sensitivity is observed at the L-band, this provides insight into why both SMOS and SMAP utilize L-band sensors for global soil moisture estimation under a range of vegetation conditions. It must be noted that measuring soil moisture at L-band has the added benefit of capturing microwave emission from deeper within the soil, typically around 5 cm, whereas C- and X-band emissions primarily originate from a thinner layer. This is feasible due to the relationship between soil moisture and soil permittivity and the connection between soil permittivity and soil emissivity. For that, the passive microwave remote sensing community has developed numerous soil dielectric models in recent decades, which, despite their differences, commonly utilize soil moisture, soil texture, and frequency. Well-known examples include Dobson, Wang & Schmugge, and Mironov. For this project, we opted for the Mironov model due to its flexibility and strong performance when utilizing the soil’s clay percentage as the sole ancillary data [Mialon et al., 2015].

It is important to note that during the soil moisture retrieval, another parameter of interest, \(𝜏\), can be retrieved. \(𝜏\) quantifies the attenuation of L-band microwave radiation by the vegetation canopy. While vegetation is typically studied using optical or infrared frequencies, the longer wavelengths of L-band sensors allow radiation to penetrate the canopy more effectively. As a result, \(𝜏\) can be linked to a variety of vegetation attributes, such as forest height, vegetation structure, water content, sap flow, and leaf fall. Furthermore, some vegetation indices, like the Leaf Area Index (LAI) and the Normalized Difference Vegetation Index (NDVI), can also be correlated with \(𝜏\). Notably, several studies have emphasized the substantial influence of soil roughness on the retrieved \(𝜏\) values at both local and regional scales [Grant et al., 2016, Fernandez-Moran et al., 2017].

Fig. 2 Sensitivity of TB to different factors across CIMR bands (adapted from [Kerr, 1996])#