Introduction, Purpose and Scope#

Snow monitoring on a global scale is an important task considering the essential role of snow in the global climate and hydrologic systems, and given the scarcity of ground-based snow observations globally. Snow has distinctive, frequency-dependent characteristics in terms of microwave emission. This enables the use of brightness temperatures as measured by spaceborne passive microwave sensors, for the estimation of terrestrial snow area (TSA) through snow detection methods. Such snow detection is moreover a preprocessing step for the global retrieval of snow water equivalent (SWE) in order to minimise uncertainties in the latter [Luojus et al., 2021]. Reliable snow detection is thus crucial not only for the estimation of TSA, but also for the quantification and trend analysis of SWE [Pulliainen et al., 2020].

Snow is a mixture of ice crystals, liquid water and air. Over time, the density of a snow pack increases due to compaction by wind and gravity, and due to thermal metamorphism. Its internal structure is characterised primarily by the grain or crystal size, and by the form and orientation of those crystals. A further property is snow wetness which refers to the liquid water content. For temperatures at or above the freezing point, a considerable amount of liquid water might be present within a ‘wet’ snowpack. For temperatures below the freezing point, on the other hand, a snowpack is unlikely to contain any liquid water and is thus considered to be ‘dry’. Below we discuss PMW remote sensing of snow with a focus on the detection of (mostly) dry snow and associated challenges.

In contrast to visible and near-infrared bands, dry snow is mostly transparent to microwave radiation. The microwave energy that is emitted from a snowpack hence originates not only from its surface, but also from deeper snow layers and from the ground beneath. For dry snow detection, the contribution in emission from the snow layer itself is most of the times negligible because of its low emissivity in comparison to the ground underneath. The emission of the ground is in turn attenuated by the snow cover, predominantly due to volume scattering. Since the magnitude of this attenuation is dependent on the microwave wavelength amongst other factors, lower brightness temperatures are measured for higher frequencies in the presence of snow. Dry snow is thus commonly detected by comparing the brightness temperatures of different frequency bands in order to identify such attenuation.

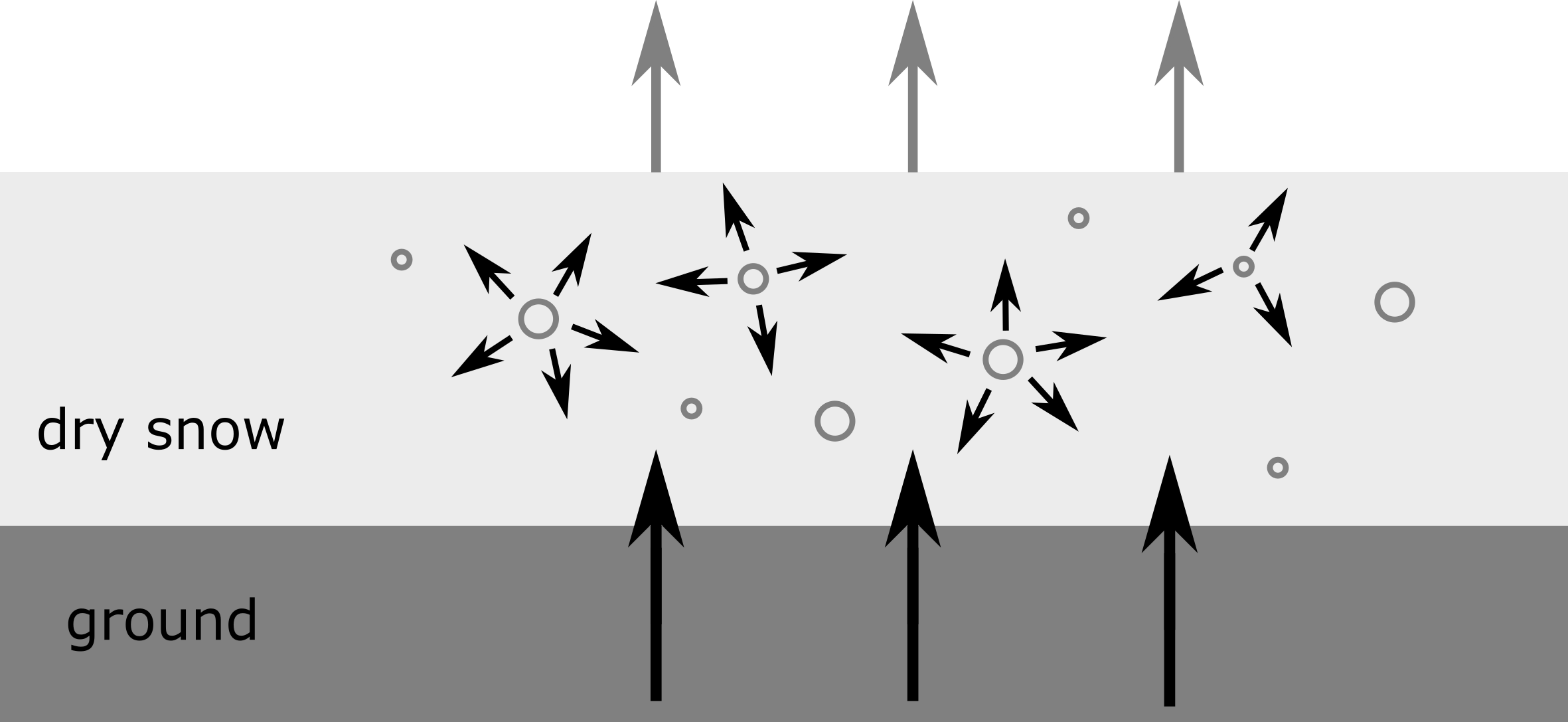

Volume scattering, the dominating type of attenuation as observed for dry snow, is highly dependent on frequency. Air acts as a surrounding medium for the ice particles with diameters on the order of millimetres. For propagating waves with wavelengths noticeably larger than this, snow appears as a homogeneous medium with only absorptive effects. For wavelengths of similar magnitude, the ice particles act as scatterers due to the inhomogeneous dielectric properties between the ice itself and the air background [Ulaby and Long, 2014]. This scattering mechanism is illustrated in Fig. 1. The phenomenon that the emissivity of snow-covered ground decreases with increasing frequency, is unique among land cover types and is directly influenced by the snow’s properties [Mätzler, 1994]. The impact of wavelength on scattering behaviour can be applied to snow grain size: the higher the frequency and/or the larger the grains, the more scattering is observed as the particle size approaches the wavelength. Snow density has a similar effect to grain size and since both generally increase for aging snow, older snowpacks result in more attenuation. A further aspect to consider is snow depth, given deeper snowpacks naturally allow for more scattering to take place.

Fig. 1 Schematic of the microwave emission from snow characterised by volume scattering.#

This attenuation found for snow-covered surfaces is detected through the difference in brightness temperature between two (or more) PMW bands. A channel of lower frequency provides a scatter-free reference brightness temperature, whereas higher frequency channels may show an attenuation in brightness temperatures due to their sensitivity to scattering. For this, the Ku and Ka-band are common respective choices [Chang et al., 1987, Foster et al., 1997, Grody and Basist, 1996, Hall et al., 2002]. Such a spectral difference, often referred to as scattering signature, is obviously sensitive to snow presence in first place as well as to snow properties and even to subnivean soil conditions [Mätzler, 1994].

This sensitivity to snow properties can be exploited to derive snow depth estimates from scattering signatures. However, snow depths of less than about 3 cm are seldomly detected because the scattering effect is only marginal [Chang et al., 1987, Hall et al., 2002]. To improve the sensitivity to thin snowpacks, brightness temperatures from high frequencies of 85 GHz and above can be included as those are subject to increased volume scattering [Grody and Basist, 1996]. In addition, the influence of the underlying ground on the observed emission is more apparent for shallow snowpacks; an increase in soil temperature and/or wetness may significantly increase the measured brightness temperature. On the other hand, snow depths corresponding to bulk SWE of about 150 mm become problematic as the maximum observable scattering is reached. This results in signal saturation i.e. snow depths cannot be reliably estimated anymore using the brightness temperature difference since no variations in scattering are present beyond this snow depth [Takala et al., 2011]. Snow is now the primary emitter, and its emissivity starts to increase rather than decrease for increasing snow depth [Foster et al., 1997, Mätzler, 1994].

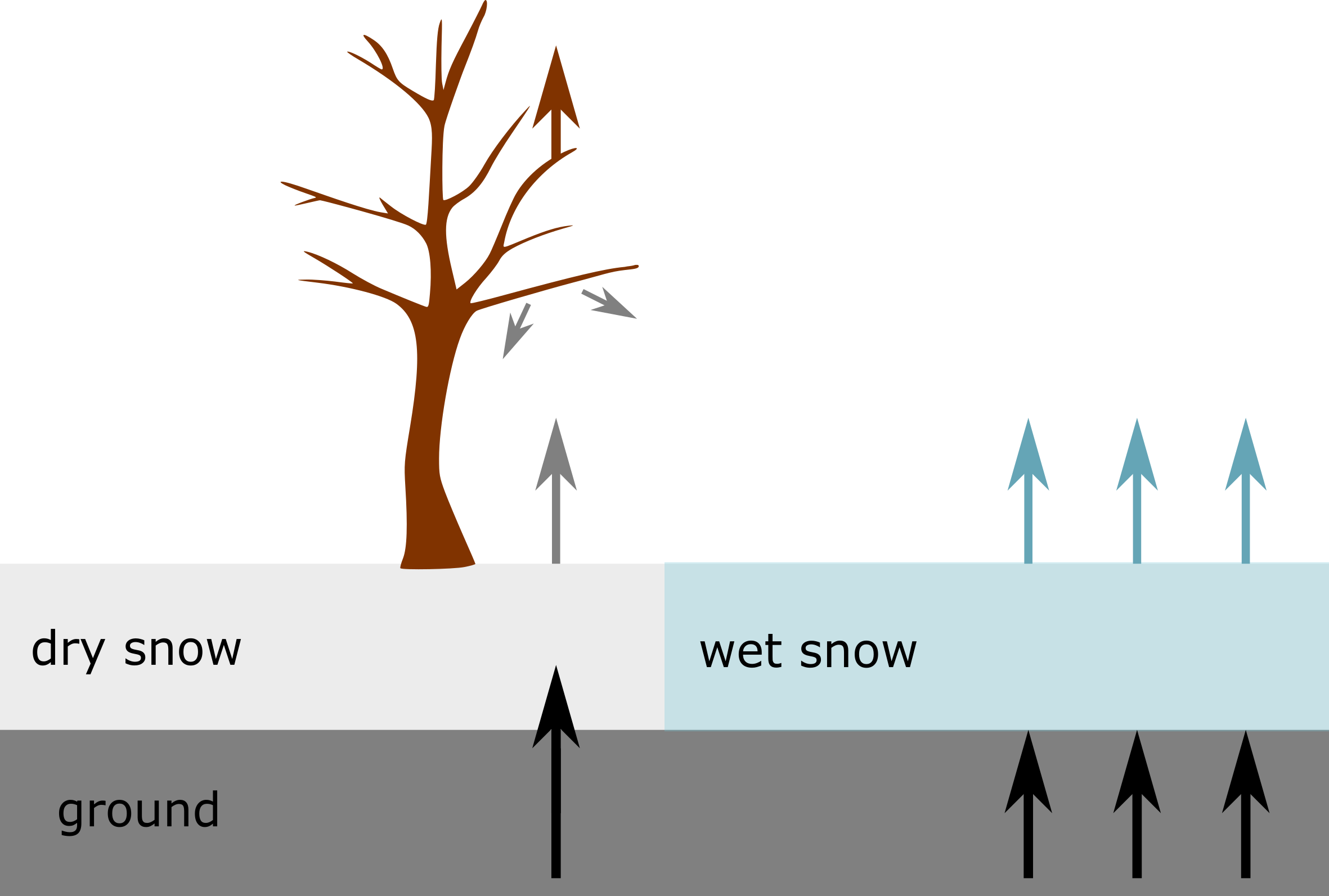

In contrast to dry snow and regardless of polarisation, consistently wet or melting snow can be hardly discriminated from bare wet or frozen soil. The liquid water content significantly reduces if not eliminates the snowpack’s transparency to microwave radiation, as shown in Fig. 2. The scattering signature as such is thus not present, and the emissivity spectrum of wet snow is hence drastically different to the one of dry snow [Mätzler, 1994]. The internal wetness of snow also affects the capability of scattering signatures for snow accumulation monitoring. Even though PMW remote sensing can be used to retrieve accumulation rates in the dry-snow zone of ice sheets, it is greatly limited by spatial and temporal variability in liquid water and refrozen subsurface ice structures, and relies highly on in situ measurements. An additional classification for glacial ice might need to be introduced since common scattering signatures for snow detection can result in a lack of scattering for large regions of Greenland and Antarctica [Grody and Basist, 1996].

Fig. 2 Schematic of the effect of ambient conditions (vegetation and liquid water content) on the microwave emission from snow.#

Liquid water similarly poses a key challenge in form of water bodies. For that reason, large waters such as oceans and large lakes are commonly masked out, as are pixels that cover large percentages of water e.g. in coastal areas or lakeland. Another problem is that most of the Earth’s seasonal snow cover occurs in complex landscapes. Firstly, mountainous terrain hinders snow detection since large spatial differences in snow depth are to be expected: whilst deep snow eventually reaches saturation depth, the signal of areas with shallow snow prevails which may be mistaken for bare ground. And secondly, the changes in slope gradient within the sensor footprint cause variations in (local) observation angle and thus in view-dependent emissivity which again may be falsely identified as snow-free conditions. Besides, overlying vegetation reflects upwelling microwave radiation and emits some on its own [Grody and Basist, 1996], as illustrated in Fig. 2. Snow cover in forested areas consequently presents higher emissivities and brightness temperatures than in unforested regions.

Limitations of dry snow detection based on the scattering signature also arise due to anomalous scattering signals, caused for instance by precipitation or cold deserts [Grody and Basist, 1996], or due to internal variations in snow properties. The latter includes variations in density and grain size resulting from the snowpack stratigraphy. Those distinctive snow layers affect more the horizontal than the vertical polarisations of the Ku and Ka-band channels [Kelly et al., 2003]. It could be derived that vertical polarisations are more appropriate for snow depth estimations given they are less responsive to internal characteristics, whilst horizontal polarisations are more sensitive to those same properties and therefore suitable for detecting dry snow in first place [Kelly et al., 2003]. Nonetheless, either polarisation have been applied for dry snow detection.

The purpose of this ATBD is to detail the implementation of the CIMR Level-2 Terrestrial Snow Area (TSA) product, in form of a binary classification. The scope is the implementation of a stable version using horizontally polarised Ka and Ku-band brightness temperatures as core frequency bands according to Hall et al. [2002] and Pulliainen et al. [2010].